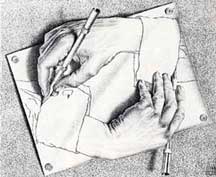

M.C. Escher Drawing Hands, 1948 www.mcescher.com

|

I have employed five modes of analysis to organize my understanding of the experiences and events that occurred during the action research initiatives at Captain Dewey High. Two modes of analysis, conversational reality theory and Ricoeurian hermeneutics are fundamental to the way I have interpreted the other three theoretics. However, for clarity’s sake, the more fundamental Ricoeurian hermeneutics and conversational reality theory will not be covered in depth until Chapter Five. Both conversational reality theory and Ricoeur’s hermeneutics are constructions based upon holistic, non-antagonistic perceptions of events. Neither theoretical discipline employs conceptual polarities as fundamental to their interpretations. In Ricoeur’s hermeneutics interpretation is the ongoing relationship an individual has with text. In the Ricoeurian view, interpretation is an attempt to establish connection with meanings made by another consciousness in textual forms. Conversational reality theory emphasizes a meaning-in-process view, a way to understand face-to-face interactions, that holds all participants responsible for creating their perceptions of events, acknowledging that individual perceptions are the result of personal experience merging into the interpersonal moment of communication. Emphasizing the role that relationship plays in meaning-making, both theories subsume polarity schemata within a relational process dynamic that assumes mutuality. In Chapter Five, I will use conversational reality theory and Ricoeurian hermeneutics to interpret three sets of polarity thinking that I observed affecting the change process at Captain Dewey High. The three sets of polarities that are covered in depth in this chapter are Carol Gilligan’s justice and care dichotomy, Third Force psychologists’ interpretation of the I and Thou relationship, and Nelson Goodman’s distinction between creative and critical thinking. My purpose in this section is to discuss the possibility that a change agent can acknowledge participants’ polarity thinking while simultaneously working with the unity that underlies the polarities. In Chapter Five, I will consider how conversational reality theory and Ricoeurian hermeneutics provided a means for me to perceive a dynamic unity embracing three sets of polarities that I perceived affecting the change process at Captain Dewey High. |

|

Carol Gilligan (1987) proposed that there were two types of moral reasoning; one based on abstract rules of justice and another based on the necessities and practicalities of caring for others. Gilligan proposed that women were more likely to use moral reasoning to preserve interpersonal relationships and quality of life (care) whereas men were more likely to base moral judgement on abstract, generalized rules of right and wrong (justice). In this study, I did not find that gender was a factor in the type of moral reasoning used by participants. I did note that participants often expressed the expectation that the school system should honor rule-based moral reasoning (justice) but teachers were expected to honor both justice and care for their students. When participants were disappointed in the school system’s handling of technology, their disappointment was expressed as a justice issue rather than as a care issue. Two examples of this preference for using justice-based moral reasoning with regard to technology issues follow. Competency tests. When I began my research activities at Captain Dewey High, teachers were required to pass a computer competency test to qualify for computers in their classrooms. Both Tower and Wiser expressed the opinion that the test was unnecessary and unfair. Principal Lightyear relied on Gold, the English teacher who was also chairperson of the DTLT, to determine who should receive computers. Gold thought that the competency test was fair and a necessary means to weed out those teachers who were "lazy" and unwilling to spend the time necessary to pass the test. At first it was unclear to me whether Gold was representing district policy. Archer, the district’s instructional technology coordinator, corroborated that the test had been required but added that district policy had recently changed to an enrollment-based model whereby teachers would receive computers for their classrooms proportionate to the number of students taught in each classroom. The position that Gold articulated to me was that the competency test was a just method of organizing computer allocation. His reasoning was that, although the test was not an accurate test of technological ability, passing the test proved a commitment to the technology program. According to Gold, the willingness to struggle with the test and conform to regulations was proof that a teacher "deserved" to have classroom computers. Teachers, both Tower and Wiser, who perceived the test as unfair, and Gold who perceived the test as necessary, were operating from an abstract justice orientation. Tower and Wiser expressed the opinion that the test was unjust, that teachers were unnecessarily burdened with learning outdated information and made to conform to a peer’s assessment of their commitment. Tower and Wiser did not criticize the test on the grounds that the district or the technology committee was not sufficiently caring for students or teachers. Gold criticized teachers for not having the discipline to conform to the rules set down by the district. Gold's criticism never implied that teachers did not care for education, innovation, technology, or their students. On the other hand, Archer, expressing to me that district policy had changed, framed this alteration as a caring change, a change that would prove that the district’s cared for student learning. Archer’s point was that instructional technology should serve students. Archer’s framing of the new district policy (that computers be allocated on the basis of student enrollment) included an element of abstract justice reasoning in that maintaining a standard ratio of students to computers throughout the district would be empirically just. However, he described the overriding purpose of the change in policy as an attempt to care for students and not simply as compliance to abstract conceptions of educational justice. Room 128. Bryght’s values were revealed to me in an early confrontation we had with one another over the use of Room 128, her computer lab. During the school year, Room 128 was used five periods out of seven by Bryght. Approximately 35 personal computers (PCs) were arranged around the perimeter of Room 128. Bryght had applied and received grants for 15 new computers but, once the computers arrived, she had had to wait for months before Carver (district technology specialist) had the time to come and set them up according to district specifications. Bryght’s new computers sat in boxes, in a small room off the library for an entire semester. Bryght argued vehemently that her students, having suffered so long with below standard computers, had the right to be the first to enjoy the benefit of the new computers. During the course of my time teaching with Bryght, I had many occasions to observe her active commitment to a care orientation. Justice for Bryght consisted ultimately in what was best for her students and in this she was a model for the new values that the district was attempting to support. However, Bryght’s expectations for herself were never that the district or other teachers would take care of her. In fact she did not expect a caring moral orientation for herself or her students who were mostly vocational and mostly non-white. Bryght was extremely flexible in relation to any unfairness in policy or procedures. If there was inequity in what was offered to her students, she would just work harder to acquire or achieve what they needed. As a role model she was exceptionally effective and I often witnessed students who were generally resistant to other teachers respond to her, seek her advice, support, and even take her criticisms seriously. Parents. I found an exception to the polarization of justice and care value systems in the actions and attitudes of many parents who worked with Captain Dewey High and the Fine Arts Academy. Parents were fundamentally concerned with caring for their children and yet they were valiant and nearly indefatigable in their defense of justice for the school, for teachers, and for programs that they considered could benefit their children or other children in the school. The parents that I worked with during the action initiatives often spoke of their own children proudly but in meetings and activities these parents remained focused on the needs of the group. There was a general assumption that what would benefit the school would benefit the individual student. The main reason the rumors that Sable and I were only interested in benefitting the academy were so destructive was that even the parents of children attending the academy preferred for the school as a whole to be the beneficiary of all community efforts. I found the consistency of the parents’ position to be remarkable and admirable. Justice and care: Further remarks. In general, participants, regardless of gender, did not expect the educational system as represented by the district bureaucracy to care about teachers. On the other hand, there was evidence of an almost universal belief that the educational system should care about students. My observation was that what teachers expected for themselves was justice but what they expected for their students was care. A moving example of this was when there was an increase in students fighting in the halls at lunchtime after the World Trade Center bombing on September 11th 2001, teachers met to discuss the problem and rejected a plan to bring more police onto the campus. Instead, teachers chose to volunteer to give up their free time at lunch to walk the halls. The increased teacher presence in the halls was a caring response, not a response based on abstract rules of discipline and the violence faded away almost immediately. Many participants expressed the view that justice in the context of a school system should be concerned primarily with protection and nurturance (generally intellectual but also and just as often mentioned, emotional and social) of students. Students at Captain Dewey High were mostly minors and there was a general perception that students were children who needed adult supervision, guidance, and support. Rule-based justice was applied to students as a last resort. However, the moral valuation of teachers and staff was not generally based on care but on evidence of shared, abstract values such as principles of peer equality, commitment to students, and hard work. |

I/It vs. I/Thou: Resisting Oppression vs. Experiencing Equality

|

In his book I and Thou (1958), Martin Buber described two ways of relating to another: I/Thou and I/It. Buber maintained that I/Thou relationships were the foundation of dialogue. Although Buber acknowledged that the I/It relationship (facing another as an object without relating as an equal) was necessary during some scientific and philosophical inquiries, Buber asserted that an I/It relationship between people always had a dehumanizing affect on both parties. Other theorists, those that Maslow (1968a, 1968b) categorized as Third Force psychologists, notably, Rogers (1962, 1967, 1977, 1980), Fromm (1941, 1947, 1956, 1976, 1977) and Maslow himself reported their observations that One’s attitude toward an Other influenced not only what can occur between the two in a conversational moment but also influenced how each viewed herself in general, affecting long-term behavior. These theorists proposed that a truly educative (in Dewey’s sense) quality to a relationship came about through egalitarian attitudes and behaviors that were hampered when participants assumed attitudes of superiority, inferiority, or feigned complete objectivity. In this study, I tried to use my attitude towards participants as a means of social creativity. By maintaining an egalitarian attitude towards participants throughout the study I hoped to affect the change process positively. The beneficial effects that I was hoping for were first, to bring about an increase in the use of technology as an integral part of the curriculum and second, to decrease participants’ personal anxiety, interpersonal resistance and both intrapersonal and interpersonal negative evaluations that might handicap our change effort. I discovered that an egalitarian relationship, even as temporary a relationship as a single conversation, required the willingness of both partners in the interaction to experience equality. Every participant was not willing to engage in egalitarian conversations with me immediately. Some participants, notably Tower and Strong (both women), did not begin our conversational experiences as equals. However, we gradually evolved co-equality and then friendship. Other participants, notably Sable, Wiser, and Bryght (all women) were open to equality from the first, allowing time to deepen and broaden our conversations with earned trust. Still other participants, notably Gold, Lightyear, and Pierce (all men) had powerful personalities and difficulty maintaining equality in conversations, often tending to adopt superior or inferior attitudes and phraseologies. Lightyear and Pierce made considerable efforts to be fair and open, clearly struggling with their own propensity to use their significant leadership abilities. Gold, however, seemed content to dominate conversationally. Another group of men, Carver, Genesis, Archer, and Prigogine, were adept at and dove immediately into egalitarian, conversational reality co-creation. Tower and Strong. The tone of my initial conversations with Strong was the polar opposite to that of my initial conversations with Tower. Strong met me with a great deal of conversational antagonism. I had to check my natural inclination to argue with her when her first words to me were critical and curt. I decided to trust the Lewinian construct that forces acting on people in the workplace are responsible for their perceptions. I looked for signs of pressures that could be acting on Strong. I was especially interested in finding out if I could do anything conversationally that could ease the effects of any negative pressures. Strong’s initial assessment of me was negative. Her perception was that I was going to make more work for her. Her reaction was to position herself as superior to me in our conversations. Her job required her to be responsible for every aspect of the physical life of the school. Indeed, we were all dependent upon her. Her attitude of superiority was based on the fact that she controlled the money and the resources that we all needed. However, the fact that she needed to meet me with that attitude was more a reaction to the fact that her burdens were overwhelming than a reflection of a genuine assessment of me or of the potentials of our relationship. The second time I needed to speak with Strong, Carver volunteered to come with me and vouch for my character and skill. Carver's introduction was a wonderful gift and typical of his interpersonal sensitivity and generosity. Although Strong was willing to give me the benefit of the doubt because a chain of positive regard had been created when Carver vouched for me, it took months to prove to Strong that I could be trusted to respect the school and her role in it. Over the course of the year and a half that I worked at Captain Dewey High, I had many opportunities to aid Strong and I did so every time. After the first few times of my showing genuine respect for her position, Strong changed her conversational attitude towards me and we began to build what became a meaningful, egalitarian, working friendship. My respect for Strong was genuine. She was dedicated, thorough, hard-working, reliable, fun-loving, responsible, csring and extremely competent. The time and effort it took to earn her trust was itself a meaningful experience for me. Tower’s initial conversational positioning was exactly opposite to that of Strong’s. Tower treated me with kid gloves. I had to work hard to convince Tower that I was operating as her equal. I found that I had first to convince her of her superiority to me in some area that mattered to her. The event/conversation that cemented Tower’s awareness of our equality (i.e. her superiority in some areas relevant to our collaboration) took place during the summer workshops when Tower took over my duties when I had to leave town. Stepping into my role brought the realization that she performed better than I could in similar circumstances. In my relationship with Tower, I carefully monitored and limited my competitive instincts in order to support her growing realization of her own autonomy in relation to technology innovations. Restraining myself in this way meant in practice never to allow myself to step in and do any work in the action initiatives that Tower could do herself even when I felt had more experience or when I preferred my own style. I did not keep my strategy secret from Tower. I shared my thinking with her by comparing my work to hers. I asked Tower if she ever gave in to the temptation to paint for her students, to solve an art problem for them. We both understood that it does very little for a creative person to have an activity done for them. It is especially important for creative people to find their own way to work: to create their own unique relationship with the medium. I explained to Tower that, although I was tempted to try and solve all her technology problems, I would not. I would give her all the room she needed, and provide support and encouragement but our collaboration would mean little to her in the long run if I did not trust her to create her own unique relationship to technology. Proportionally, over the two years, I spent more time with Tower and her students than I did with anyone else at Captain Dewey High; and the improvement in Tower’s curricular use of technology was greater than anyone else’s I worked with during the same period of time. But I did very little other than simply be there, providing just-in-time support, information, and sharing genuine affection through meaningful conversations. When Principal Lightyear arranged to have two new computers put into Tower's room, then, at Tower’s request I worked several times a week, several periods each day, tutoring students in how to use Photoshop so that they could function as peer mentors for their classmates. Gender factors. Although in most instances the women participants in this study were more sensitive to I/Thou relationship dynamics than the men, this was not the case in every instance. Probably because the nature of the study involved my interest in how conversation would affect a change process, participants who were attracted to working with me tended to be sensitive to conversation and issues of interpersonal relating. For instance, Genesis, Carver, Archer, Lightyear, and Pierce (all men) were self-consciously aware of their role in interpersonal relationships. These men were not only aware of an official responsibility to be fair in their treatment of others, I observed them all actively co-creating equality with a variety of conversants. It took me awhile to realize that one of the reasons that Gold was able to make so much trouble in meetings was that the other men’s sensitivity to issues of inclusion made them strategically unsure as to an acceptable way to restrain Gold’s overbearing conversational aggressiveness without themselves becoming equally aggressive. In contrast, the women participants tended to support polarization in I/Thou relationships. Often, even while being sensitive to the dynamics of care in conversations, I observed women participants actively maintaining social hierarchies in conversations, especially but not exclusively, with men. Several times, my role as change agent required me to model interpersonal conversational styles that self-consciously ignored hierarchical or sexist considerations, concentrating instead on specific issues and the importance of individual's self-representation. Interestingly, most of the women participants were able to alter their conversational role almost immediately after witnessing my behavior. I never told or even suggested to women participants how to act but I did discuss with them my feelings of hurt or outrage when I witnessed people overwhelming others in a conversational dynamic. The participants whose conversational styles were most unique in this study were Gold and Wiser. Wiser had a unique way of conversing that utilized traditional female pliability while maintaining her authority. She was spontaneous and yet rarely lost command of conversations or their contexts. Wiser credited her conversational skill to her mentor, a (male) high school teacher at Captain Dewey High who had been her teacher and then became her mentor when she returned to Captain Dewey High as a teacher herself. Wiser attributed her phenomenal ability to use conversation to continuously teach and learn as fundamental to her role as a teacher. Gold was an anomaly at Captain Dewey High. Participants spoke well of Gold’s teaching ability and of his reliability. Gold, however, was feared. His punitive attitudes and actions pushed many teachers away from him and he did not seem to notice or mind that teachers did not come to him for help. Gold was probably the member of his staff most committed to technology innovation in the school; unfortunately Gold could not help others make that same commitment. I and Thou: Further remarks. The effect that interpersonal attitudes had on the change process is inestimable because the attitudes that participants had towards one another and towards me as technology change/integration agent were embedded in every interaction that took place among us. The patterns that I observed were consistent with the theories of Third Force psychologists that egalitarian conversation can inspire action consistent with its philosophical premise. And the obverse was observed as well, that hierarchical attitudes displayed in conversation inspired actions consistent with perceptions of inferiority and superiority but not equality. In this study, I found that a consistent positioning on the part of the action researcher to practice, model, assert (and reassert if necessary) her equality with others was efficacious in several ways. First, the core participants (including myself) increased our positive self-evaluations. Second, the core participants, who were all women — Sable, Tower, Wiser, and Bryght — gained increased respect from one another and also from some of the male participants, notably Lightyear and Pierce. We gained increased respect not only because of our accomplishments but because of the egalitarian way that we came to express ourselves in meetings and in our strategic actions. We also gained each other’s trust and friendship, the value of which is incalculable. |

Critical and Creative Thinking

|

In his own life, Nelson Goodman (1978) set an example of the theory he espoused, that creative and critical thinking work in partnership at thought’s higher levels of achievement, particularly when thought is understood as a precursor to action. A significant portion of my time at Captain Dewey High was spent encouraging participants to integrate creative and critical aspects of their thinking and/or to acknowledge that they had already integrated these methods of thought. A dynamic relationship between creative and critical thinking is useful in any change effort and certainly in this case study proved valuable in co-determining ways to integrate technology into the curriculum. Art and science. Pierce was influential at Captain Dewey High not only because he headed the Fine Arts Technology Committee but even more because he was a sensible, honest, hard-working parent who could be relied upon to do a thorough job on any project. The first time I met Pierce I was struck by his charm. Further meetings, conversations, and e-mails revealed Pierce to be not only charming but tenacious. Occasionally I found myself "pushing back" against the force of Pierce's personality and strong opinions. Pierce never reacted emotionally or negatively when I "pushed back;" rather my standing up for my opinions and asserting my personality usually brought about a thoughtfulness and a deeper conversational considerateness on Pierce's part. I greatly admired Pierce for being strong and flexible and especially for being able to accept and enjoy strength in others. However, I never witnessed either Pierce, Lightyear, or Gold abandon strategic conversational positioning for collaborative, freewheeling brainstorming. To confuse the gender discussion even further, Genesis, Carver, and Archer (all men) were adept at collaborative, conversational brainstorming. When Tower expressed to me that she was having difficulty gaining Pierce's trust, she described a scenario that was believable to me. Tower said that when she offered ideas in meetings, Pierce did not seem to take them seriously. Tower had a delicacy, an ethics in her approach to people and ideas that made it onerous for her to try and overpower another person. First, I tried a straightforward strategy of simply telling Pierce whenever we were alone how much I respected Tower's ability and intelligence (essentially the same strategy that Carver had used when he introduced me to Strong). A few weeks later, I asked Tower if she noticed any difference in the way Pierce listened to her. The answer was no. I then tried another straightforward strategy: describing to Tower the sort of behavior that I had used to get Pierce's attention and respect. Unfortunately, or perhaps fortunately, people do not easily alter their style of communication. During the fine arts’ parents’ booster club meeting (described in the description section of this chapter) I was able to describe some of Tower's views in a way that Pierce could understand. I do not believe that Tower and Pierce will have an easy time learning to communicate in a trusting manner or a truly collaborative manner. If they continue to work together over a period of years, they may reach an understanding. However, their training is diametrically opposed and, because they are both experts in their fields, there is little likelihood that either of them will abandon their methods of inquiry or delivery. What was it about their areas of expertise that made it so difficult for Pierce and Tower to communicate? Pierce was a successful engineer. He owned his own company. Tower was an accomplished painter. She taught art. They each approached problems in a way suited to their profession. Pierce, primarily a critical thinker, organized his ideas and then worked on them one at a time until he had accomplished his goals. Tower, primarily a creative thinker, perceived a general situational imperative and alternately applied activity and analysis to the situation and then intensely self-reflected on the results. Essentially, Pierce used scientific rationality and Tower used creative reasoning; and as yet there are few disciplines in our culture that bridge the gap between these two types of thought/action methodologies. Although it would be temptingly tidy to attribute modes of reasoning to the gender of participants, I have not observed the creative/critical difference in approach to problem solving manifesting along gender lines but often because of a difference in educational background (however, gender does often influence choice of vocation). In other words, in my experience, educated people tend to reason the way they were taught to reason. It fascinates me that the area that brought Tower and Pierce into relationship was technology. It is my view that communication technology not only demands both types of reasoning but will be a medium for the creation of a variety of bridges and bridging techniques between these as yet dichotomous patterns of thought and praxis. Tower and Pierce have achieved significant improvements in the Fine Arts Academy and there is every evidence that they will continue to do so. Their struggle to communicate is part of the school change process as well as part of a national and international cultural shift, an ongoing creation and recreation of cultural and conversational patterns now influenced by technology integration into our daily lives. Music and literature. The arts and the humanities are not immune to fractures in the social fabric due to the schematic polarization of creative and critical thinking paradigms. The following description of a particular conversational confrontation that took place during this study serves as an example of the polarization between creative disciplines due to each discipline's epistemological reliance on specific types of critical rationality and creative praxis. I disagree with Bruner's position described in Narrative and Paradigmatic Modes of Thought (1985) that there is a scientific paradigm that can be juxtaposed to a narrative consciousness that is somehow free from paradigmatic restrictions. I agree with Cassirer (1955c) that, as all thought is based on symbols, communicable thought must be paradigmatic (i.e. reference previous forms and patterns) in order to be understood. I have observed that there are many narrative paradigms that affect interpersonal interactions and there is considerable evidence that cultural narratives (paradigms) influence scientific paradigms and bind social and conversational reality to predetermined forms (Apple, 1982; Freire, 1993; Gersie, 1997; Tannen, 1986, 1993a, 1998). Lightyear was an English teacher before becoming the principal of Captain Dewey High. Lightyear was also a poet. Sable was a music teacher and at the time of the study was the conductor of a prestigious city choir. One might be tempted to assume that people trained in these two art disciplines - literature and music - would have an easy time communicating, but in practice the types of intelligence (Gardner, 1983), and the epistemological structures (Hirst, 1974) used in practicing these two art forms are quite different. The most emotionally volatile conversation that occurred during the entire action research experience was a conversation between myself, Lightyear, and Sable. The issues we were discussing had been precipitated by Gold's behind-the-scenes accusations that Sable and I were intending to undermine teacher authority by taking classroom computers without their permission. Another rumor was spread along with the story that Sable and I were intending to confiscate computers: This second rumor was that I was not qualified to be working in the school at all but had been brought in by Sable, under false pretenses, without Lightyear's knowledge or permission to benefit the academy, to the detriment of the school as a whole. Lightyear told Sable and myself that he was "concerned" with the negativity that had come to his attention concerning our summer technology workshops. Lightyear developed a story that implied that he was a neutral actor in the events that had taken place and that Sable was responsible for any negativity that had been directed at me. I challenged Lightyear's narrative by offering an alternative narrative, based on a different set of symbolic paradigms. My story was that Lightyear’s pose of neutrality had made it possible for Gold and others to believe that Sable was acting alone. Lightyear knew how many meetings we had attended to get permission to do the action research projects because he had required us to attend them. Lightyear also knew that he had signed and approved every aspect of the grant administration. He, himself, in a private meeting, had asked me if I would please take over Carver’s position and co-administer the grant. Instead of showing gratitude to Sable for following through on the details necessary to fulfill the terms of the grant (for which Lightyear was the sole signator), Lightyear had chosen to keep silent. My contention was that, in his role as principal, Lightyear could have participated actively, conversationally, influencing the opinions and perceptions that Gold and other teachers had created out of fear and lack of information. Note that Lightyear’s duties were immense and some of his "silence" on these issues may have been caused simply by having been too busy with more pressing crises to notice ours in the making. Lightyear was a good listener and an excellent administrator. He did not respond to my challenge with anger or denial. He praised me for my courage in speaking up. Lightyear had then initiated a move away from a critical, rational narrative and placed us soundly on the ground of creative, mutual appreciation. Sable had not said a word. She had not said anything in her own defense when Lightyear had earlier implied that she had not been particularly competent in her dealings with others. And, as I defended her she seemed surprised. Encouraged by Lightyear’s example, I said that I had seen Sable's choir in concert before I had ever met her. I said that anyone who could work with so many people and combine so many voices and personalities into one uplifting musical experience could not possibly be less than competent in interpersonal relating. I had literally danced out of that concert, leaping and singing. My experience working with Sable was that she was capable of handling people of all kinds. She found ways of supporting people, allowing them to make their unique contribution, while, at the same time, she was able to bring our work into a unified whole. I knew, as I spoke, that Lightyear had not heard Sable described in this way before. I never asked Sable or Lightyear if that conversation changed anything. At that time I was not thinking as a change agent and researcher, I was deeply immersed in the narrative of the school and I was swept away by the situation to make utterances deeply, personally meaningful to me. And yet this is the conversation I feel most pride in having co-created because this conversation brought about a deeper trust between us and a greater efficacy in our ability to create lasting change in the school. An exception: Appreciation of complementarity. Wiser was a master teacher and able to appreciate, converse, and work with whatever mode of inquiry was necessary to create a learning environment that was supportive of her students. I was witness to many instances of Wiser's flexible utilization of creative and critical thinking. In one particular, informal interview, Wiser acknowledged that her goal for her students was to teach them how to think critically about their creativity. She felt that she had seen over the years that the students who succeeded in further education were able to organize their ideas. I wish my words could conjure up the gentle, firm, imaginative manner in which Wiser gradually led her students to a balance between personal expressiveness and critical awareness. Genesis was another teacher who was able to model and encourage a synthesis of creative and critical intelligence. As Head Librarian, he was able to influence not only students but teachers. Carver, a good friend of Wiser, Strong, Genesis, and Bryght was also able to combine these two modes of intelligence, making him popular with so many of people he worked with throughout the district. I came to depend on Wiser, Genesis, and Carver for moral support. Even though, of the three, only Wiser was a core participant, I cannot imagine that the action initiatives would have been as successful as they were without all their considered and considerable support and their active intervention in events. These exceptional people not only personally guided me throughout the projects but they made it known to others in the school that I was working with them. These associations contributed to my personal growth and my professional skill. Wiser, Genesis, Carver, and I did not use technology simply as an extension of our analytical intelligence. And, although we shared a vision of technology as supporting all school activities, however powerful technology becomes in education, none of us felt that technology should or could ever replace interpersonal involvement in education. |

Polarity Thinking and Teacher Resistance to Change

|

Argyris (1982), in his description of double loop learning, made a distinction between "theories-in-use" and "espoused theories." According to Argyris, people often exhibit behavior that does not conform to the theories that they report to believe. In my study, resistance to technology was an espoused theory of those responsible for the allocation of hardware and the dissemination of information pertinent to instructional technology. But, if Gold had not understood that teachers were using the computers in their classrooms, then he would not have used the threat of the removal of computers to try and harm my reputation as change agent, nor would he have used the threat of the confiscation of computers as a punishment for failing to pass the competency test. In other words, Gold's theory-in-use was that teachers were using, not resisting, computer technology but his espoused theory was that teachers were resistant to technology. A popular espoused theory at Captain Dewey High was that rule-based reasoning was the means through which educational value was distributed but the theory-in-use that I observed staff, teachers, and parents use most often was care-based, moral reasoning. Another espoused theory in the school was that different pedagogical areas were in competition for scarce resources but the theory-in-use that I most often observed was cooperation and a willingness to share resources if students were to benefit. Polarity thinking exacerbated the rift between espoused theories and theories-in-use. My conversational work with the core participants (Sable, Wiser, Tower, and later, Bryght) often focused on initiating discussions that would allow us to perceive polarities as elements of working, unified systems. Humor was an invaluable tool for weakening the hold that polarity thinking had on the minds and hearts of the core participants and we used it often, finding joy in each other’s presence and the knowledge that life will always provide us with challenges is mitigated by the awareness that we are not facing them alone. Argyris (1982) implied that there was an element of hypocrisy involved in the rift of reasoning dividing theories-in-use from espoused theories. However, I found that if participants were able to come to an awareness of the limitations inherent in allowing one's theories-in-use to become polarized from one's espoused theories, they were quite willing to re-evaluate their thinking and bring their theories into closer correspondence. Bringing theories-in-use into alignment with espoused theories can bring more intellectual energy to bear on action and makes the resultant action more effective than if these theory sets are operationally or philosophically polarized. The conflict between creative and critical thinking was the polarization that most restricted the technology change process at Captain Dewey High. Participants who were more comfortable thinking creatively were frustrated by the linear thinking of some technology specialists. And some more flexible technology specialists were frustrated by teachers trained in only one approach to thinking. Participants who were more comfortable thinking critically were often frustrated when participants were communicating with emotional resonance about relational complexities. And creative thinkers were often distressed by bureaucratic rationalizations that restricted teacher ability to engage with students effectively. I found that teachers showed a natural hesitancy to engage in dialogue that might reveal a professional weakness, especially in front of students. This hesitancy could be interpreted as resistance to change but I observed this form of hesitancy or resistance at different times from everyone involved in my study and I imagine that I myself, at times, showed signs of a similar hesitancy. I did not find that teachers were resistant to change per se, rather I found that teachers were guarded, first, when they thought that they might look incompetent in the process of acquiring new knowledge, and second, teachers resisted any change that they thought might negatively affect their students. When a participant was convinced that a technological innovation would not endanger their self-esteem or their relationship to students, the change process was encouraged, not resisted. A final note. If I could share only one impression of my experience at Captain Dewey High with the research community it would be that teachers and school staff need more of everything. Teachers need more time, more money, more support, more training, more benefits, more time off, and most importantly, teachers need more respect, conversation, and genuine collaboration. In this study, mutuality of exchange and a genuine respect shared between technology professionals and teaching professionals mitigated teacher resistance to technology. While researching at Captain Dewey High I wrote in my journal that "Democracy as we dream it has yet to be invented, and can only be realized as a process, [as] the experience of being equal among equals. We can never write about this enough." |

home* chapter one* chapter two* chapter three* chapter four* chapter five* table of contents*